Archive for 2012

Lab page is up!

Well, I’ve been buying Cisco equipment for some time now and I figured I finally got enough that I can show it off. I started off with a 3745 from a friend and two 2960’s I got from a good deal and slowly added some more routers. My end goal for this lab is to be capable of configuring anything I need whether it’s for studying or work related and I need build a customer network.

I’ll be adding even more as time goes on, and soon enough I will have enough to start labbing for the CCIE!

IPSec on a Cisco IOS router.

In my previous post I covered some basics on IKE and the process on which IPSec VPN’s form and negotiate their secure connection. So now I figured I’d continue that trend and cover the configuration of an IPSec VPN between 2 Cisco IOS routers.

So let’s check out a large portion of the configuration right here:

This configuration snippet (the first 3 lines) includes the ISAKMP policy used in phase 1 negotiations, which specifies the encryption, hash, & authentication method. I also want to mention you can have multiple ISAKMP polices on the same router, the thing to remember is the ISAKMP policies will be negoatiated from the top down. So the first ISAKMP policy that matches the peer’s ISAKMP profile with the lowest sequence number is the policy that will be used. Which means it is best practice to place the more secure ISAKMP policies at the beginning of your policy, to ensure they get used over a weaker policy.

Right after the ISAKMP policy we have our PSK used to authenticate the specific peer. You can specify the address 0.0.0.0 0.0.0.0 to use the same key for all IPSec negotiations. So you would not need to specify a PSK for every particular peer.

Next we have our transform-set which provides us with our encryption options for phase 2 negotiations. Within the transform-set is were we can specify the encapsulation mode (tunnel or transport). Similar to the ISAKMP policy we can configure multiple transform-sets with completely different parameters in each one.

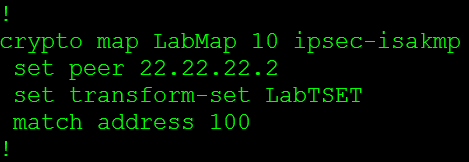

Now the Crypto Map is where we tie in a lot of these parameters and start linking it to the peer. The first thing we set is the peer’s address, and then we will specify the transform-set that will be used with this particular connection. I want to mention we can configure multiple transform-sets for a single peer and during the negotiations a matching transform-set will be used. The last thing in this crypto-map is the match address 100 this is where we specify what traffic gets encrypted, this is known as interesting traffic. This matches to an ACL.

So all traffic that goes between the 192.168.1.0/24 and the 192.168.2.0/24 network will get encrypted.

Now the last thing we need to do is apply that crypto map to physical interface.

Now we can only have a single crypto map applied to a physical interface, so the next question is how do we configure multiple VPNs to terminate to a single router? Well we configure multiple entries using the same crypto map, we do this by using a different sequence number for each peer.

So from the above screen shot the sequence number after the crypto map is different, these sequence numbers can go from 1 – 65355 so you have more then enough sequence numbers to terminate multiple IPSec VPNs to a router. Of course you will never want to terminate 65355’s VPNs to a single due to performance.

The next thing I want to mention is how to configure a single crypto map to form VPNs using main mode or aggressive mode. This might sounds tricky at first since you can only have a single crypto map assigned to a single interface but it’s really pretty simple, all you have to do is use the same name you used for the existing crypto map.

So to recap the pieces we need to create a policy based IPSec VPN

- The ISAKMP Policy

- The Transforms-Set

- The Pre-shared key

- The Crypto Map

- Access-list

IKE main mode, aggressive mode, & phase 2.

Just like GRE tunnels, IPSec is found in every single network, whether it’s in the form a Lan2Lan tunnel or a client side remote access VPN. We all know IPSec secures communication between two endpoints using ISAKMP, Diffie-Hellman, and various other encryption and hashing algorithms but how exactly do these protocols work together. We know IPSec will form its tunnel after IKE Phase 1 and Phase 2 so let’s take a look at what goes on during this process:

IKE Phase 1

IKE Phase 1 works in one of two modes, main mode or aggressive mode now of course both of these modes operate differently and we will cover both of these modes.

Main Mode:

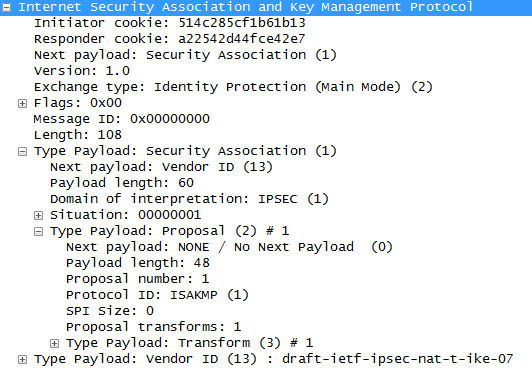

IKE Phase 1 operating in main mode works with both parties exchanging a total of 6 packets, that’s right 6 packets is all it takes to complete phase 1.

- The first packet is sent from the initiator of the IPSec tunnel to its remote endpoint, this packet contains the ISAKMP policy

- The second packet is sent from the remote endpoint back to the initiator, this packet will be the exact same information matching the ISAKMP policy sent by the initiator.

- The third packet is sent from the initiator to the remote endpoint, this packet contains the Key Exchange payload and the Nonce payload, the purpose of this packet is generate the information for the DH secret key

- This fourth packet as you would expect comes from the remote endpoint back to initiator and contains the remote endpoints Key Exchange and Nonce payload.

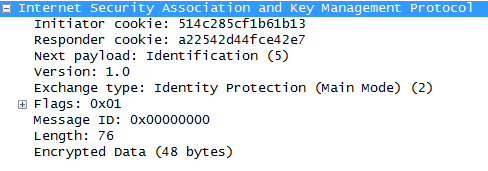

- The fifth packet is from the initiator back to the remote endpoint with identity and hash payloads, the identity payload has the device’s IP Address in, and the hash payload is a combination of keys (including a PSK, if PSK authentication is used)

- The sixth packet from the remote endpoint to the initiator contains the corresponding hash payloads to verify the exchange.

Aggressive Mode:

IKE Phase 1 operating in aggressive mode only exchanges 3 packets compared to the 6 packets used in main mode. One downside in aggressive is the fact it not as secure as main mode.

- The first packet from the initiator contains enough information for the remote endpoint to generate its DH secret, so this one packet is equivalent to the first four packets in main mode.

- The second packet from the remote endpoint back to the initiator contains its DH secret

- The third packet from the initiator includes identity and hash payloads. After the remote endpoint receives this packet it simply calculates its hash payload and verifies it matches, if it matches then phase one is established.

IKE Phase 2

Now let’s look at IKE Phase 2, IKE Phase 2 occurs after phase 1 and is also known as quick mode and this process is only 3 packets.

- Perfect Forward Secrecy PFS, if PFS is configured on both endpoints the will generate a new DH key for phase 2/quick mode.

- Contained in this first packet from the initiator to the remote device are some of the hashes/keys negotiated from phase 1, along with some IPSec parameters IE: Encapsulation (ESP or AH), HMAC, DH-group, and the mode (tunnel or transport)

- The second packet contains the remote endpoint’s response with matching IPSec parameters.

- The last packet is sent to the remote device to verify the other device is still there and is an active peer.

That last packet concludes the forming an IPSec tunnel and the phase 1/2 process.

- Note: These 3 quick mode packets are encrypted

First Hop Redundancy Protocol: VRRP

First hop redundancy protocols are important to any network, after all why should any carefully designed network be dependent on any single IP address or any single device for that matter? A FHRP allows us to make the default gateway for any subnet a virtual address that can float between multiple physical devices. However some of our FHRP choices are Cisco proprietary (IE: HSRP & GLBP), and recently I had to setup a FHRP between a Cisco router and Red Hat box, so VRRP was my FHRP of choice.

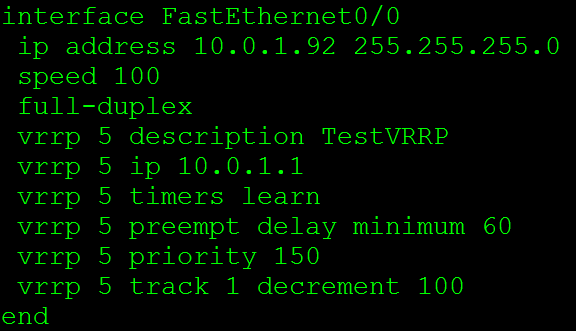

Now the configuration for VRRP for the Cisco side:

The VRRP 5 commands are what makes this happen. VRRP 5 is the VRRP group (and the router ID) this instance belongs to, next we have VRRP 5 IP 10.0.1.1 this where we specify the virtual IP address. This is going to the IP Address we want to ensure is available to our clients such as a default gateway. The VRRP 5 timers learn command tells this router to learn the VRRP advertisement timers from the master router. Next we have the VRRP 5 preempt delay minimum 60 this specifies a set of time in seconds before the master role is taken back.

Delaying the preempt may not appear to be inviting at first but it is useful. Let’s say the master comes back online and it resumes the role of the default gateway before it has had time to re-converge it’s routing table, well the VRRP master is now going to black hole traffic until your routing protocol re-converges.

Next we have VRRP 5 priority 150 this allows us to specify the priority of each router to control who will be the master router and who will be the backup router. The device with the highest priority is the device that will be the master router for VRRP. The final line in this configuration is the VRRP 5 track 1 decrement 100 command, this allows us to tie some type of tracking or IP SLA monitoring into the VRRP configuration. This way if the IP SLA or tracking mechanism goes down the VRRP priority will automatically be decremented ensuring this device will not be the master. After all, if the master VRRP router looses connectivity to the rest of the network due to an interface failure or link failure we don’t want it to be the master router anymore.

Let’s also go a step further an think about the preempt delay we spoke about earlier, lets say we set the preempt delay to 60 seconds and we are tracking the outside interface the preempt delay will make sure the outgoing interface is stable for at least 60 seconds before taking back its master role, now that preempt delay isn’t looking so bad now is it?

Now let’s verify our VRRP configuration using the show vrrp command:

This will show the current state of this router in the VRRP process, that state will either be Init, backup, or master. The Init state just mean VRRP is not running or is starting up. Next we see the virtual IP and the virtual MAC address, a VRRP virtual MAC address will start with 00:00:5E:00:01:XX where XX is going to be the Virtual Router ID (or VRRP process ID) Then we will see the preemption settings and our advertisement intervals. So the Show VRRP command provides us a nice summary of our VRRP configuration.

Now let’s check out some debug logs for VRRP:

The first message in there states the router received an advertisement with a priority of 150 from IP 10.0.1.92, then the VRRP event states that this priority is higher or equal to it’s own priority, the next advertisement has a priority of 0, and then the Master down timer expires, which causes the this router to become the master. The last few VRRP message show advertisements going with checksums, which is normal for VRRP operations.

I also figured I would show a VRRP Packet:

From here we can see the VRRP version currently running on the router. This will also show us the Virtual Router ID, and the IP address we are advertising along with the priority of the 10.0.1.92 host. Also check out the Layer 2 information Wireshark identifies that the MAC address is associated with VRRP and knows the Router ID is 5. Now check out the Layer 3 IP destination, it’s 224.0.0.18 so these advertisements are sent out via Multicast to all VRRP routers on this LAN.

More information on VRRP can be found in RFC 3768, note this RFC is for VRRPv2. RFC 5798 covers VRRPv3, but this post covers VRRPv2 running on Cisco routers. Cisco also has few articles to go over the configuration: VRRP & Configuring VRRP

You don’t have to block ICMP completely.

This is something that I typically see all over the place, security administrators blocking the ICMP (Ping) protocol completely. Normally I am ok with that, after all ping is a troubleshooting tool and in some cases not the best troubleshooting tool to rely on. However, it’s when people think their network is more secure when they have blocked ICMP. The truth is you can actually allow the ICMP types that are required for troubleshooting purposes without compromising security. So let’s first consider what ICMP messages we typically use for troubleshooting:

- Echo Request – ICMP Type 8 Code 0

- Echo Replies – ICMP Type 0 Code 0

- Time Exceeded – ICMP Type 11 Code 0

- Fragment needed but DF bit set – ICMP Type 3 Code 4

Now we all know the echo request is the icmp packet from the host to the target, and the echo reply is response from target back to the host. The time exceeded packet is returned to the host when performing a traceroute. The fragment needed but DF bit set packet is used for path MTU discovery and can used to troubleshoot MTU issues, it basically replies back telling you the packet was dropped because it needed to be fragment but the DF (Do not fragment) bit was set on the packet so it could not be fragmented.

One ICMP parameter that should be blocked are ICMP fragments, fragmented ICMP packets can be used to cause DoS attacks. Remember ICMP packets typically send 64 bytes of data, so you should only see larger ICMP packets or expect fragments when testing MTU. (Other then that I can’t think of any other legit reason to see large ICMP packets). RFC 1858 goes pretty in depth concerning the danger of IP Fragments, it’s definitely worth a read.

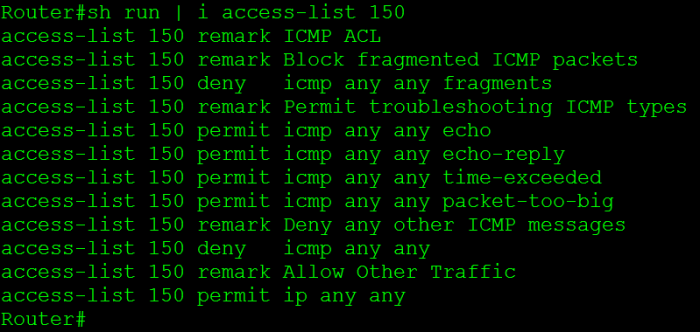

Now here is a configuration snippet that accomplishes everything I discussed here:

Now if you want to learn about ICMP in greater detail check out RFC 792.

Let’s look at Generic Routing Encapsulation (GRE)

Generic Routing Encapsulation, not much to say about it, its generic right? Well, it’s pretty tough to find a network that does not utilize GRE tunnels in one way, shape, or form. Whether they are Encrypted GRE tunnels or GRE tunnels riding over IPSec tunnels for branch connectivity chances are GRE is being used somewhere in your network. After all GRE provides us with various features that traditional IPSec tunnels do not offer us. Such as allowing multicast traffic to traverse the tunnel providing us scalability with the use of a routing protocol. It provides us these features because of how it interacts with the IP packet, some people refer to GRE as a layer 3.5 protocol because of how it encapsulates the existing layer 3 IP packet.

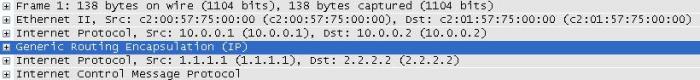

Below we can see how GRE interacts with the IP packet:

Notice you can see two sets of IP address in that packet, the first set of IP addresses (10.0.0.1 & 10.0.0.2) are the tunnel addresses, the second set of addresses under the GRE header is the real data that was sent through the tunnel, and it’s simple ICMP echo request from 1.1.1.1 to 2.2.2.2.

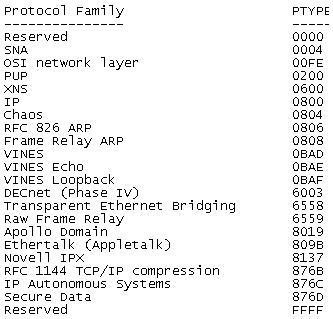

And for a closer at the fields within the GRE encapsulation.

Also notice the protocol type at the bottom, GRE can be used to encapsulate more than just IP Packets SNA, IPX, Appletalk and quite a few others can also be encapsulated with GRE.

More information can be in RFC 2784 which explains the IP Packet fields in greater detail then I covered here.

Now, as far as how the configuration goes for a normal GRE tunnel goes it is fairly minimal:

However, there are a few things that can be a little rough to get the hang of at first. The first thing unlike physical interface you can declare tunnel interfaces from configuration mode and you can start at any number. Now like any other interface you will want to assign your tunnel its own IP address since these GRE tunnels operate around layer 3 they will need IP addresses on the same subnet so both tunnel interfaces can communicate. The only other requirements for configuring a GRE tunnel is specifying the tunnel source and the tunnel destination. The tunnel source can be a physical interface or an IP address just keep in mind the tunnel source needs to be local on the router. The tunnel destination is going to the address of the remote router you are terminating the tunnel to. You will want to make sure the tunnel source and tunnel destination configured have connectivity to each other since it is between these addresses the GRE tunnel will run over.

There you go, GRE in a nutshell!